Expert Q&A: DSM-5 and ASD

Dr. Chung discusses the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for autism, how the understanding of autism has evolved and benefits of a formal diagnosis

By Peter J. Chung, MD, FAAPDr. Chung is the associate clinical professor of pediatrics and the medical director of the Center for Autism and Neurodevelopmental Disorders at University of California, Irvine, an Autism-Speaks supported Autism Care Network site.

Understanding and diagnosing autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a constantly evolving process. Thanks to years of research, our understanding of ASD has grown dramatically, leading to significant changes in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the manual published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and used by clinicians to diagnose autism and other disorders.

How has the understanding of autism evolved from the DSM-IV to the DSM-5?

The DSM is published by the APA and serves as the “rulebook” for diagnosing mental conditions, including autism. It is revised periodically to incorporate the newest research findings and evolving notions of the human brain. However, it can take a significant amount of time for each revision to be completed. For example, the DSM-IV was published in 1984 and revised in 2000. It wasn’t until 2013 that the current version of the DSM, the DSM-5, was published.

The DSM-5 made some major changes to the diagnosis of autism from earlier versions. Most notably, it removed the previous diagnosis of pervasive developmental disorders and its subtypes (autistic disorder, Asperger’s disorder, Rett Syndrome, Child Disintegrative Disorder and pervasive developmental disorder—not otherwise specified [PDD-NOS]) and formally created the diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. This change was made to acknowledge the understanding that these categories were describing symptoms under the same umbrella rather than different disorders altogether.

What are the diagnostic criteria for ASD in the DSM-5? What are the three levels of support?

The DSM-5 revised the symptoms that were required to make a diagnosis of ASD, combining the separate social and communication domains to a single social-communication domain and adding sensory symptoms as a diagnostic criterion. It also created a new diagnosis of social communication disorder (SCD) for individuals who have social-communication issues but no restrictive or repetitive patterns of behavior, interests or activities (RRBs).

As ASD is now considered part of a spectrum, the DSM-5 also includes three levels of support needs to differentiate patients under the diagnostic umbrella. Levels can be assigned for each symptom and break down into “mild” (requiring support), “moderate” (requiring substantial support) and “severe” (requiring very substantial support).

An individual can have different levels of support needs for each symptom. For example, a person who has very limited communication ability but is generally very flexible may qualify as “severe” for social communication and “mild” or “moderate” for RRB. There is no single test to determine symptom levels. Clinicians may use a variety of sources of information, including parent, teacher and self-report; direct clinical observations; need for and response to therapies, including medications; and daily adaptive needs, among others.

Level of support needs can change over the course of an individual’s life in response to therapy and natural development, and so they should be reassessed and updated periodically. In my opinion, these levels should be used primarily for tracking purposes and shouldn’t be used by themselves to determine the kinds or amount of support an individual should receive. For example, I don’t think a child who has “mild” symptoms should necessarily qualify for fewer hours of therapy than a child with “moderate” symptoms. No single value can encapsulate the unique strengths and challenges an individual with ASD can experience; each case needs to be approached at the individual level.

What do these changes mean for people with a long-standing autism diagnosis?

Research shows that vast majority of individuals who had been diagnosed with autistic disorder, Asperger syndrome or PDD-NOS would fall under the DSM-5 diagnosis of ASD. Individuals who no longer meet criteria for ASD often fall under the new category of SCD.

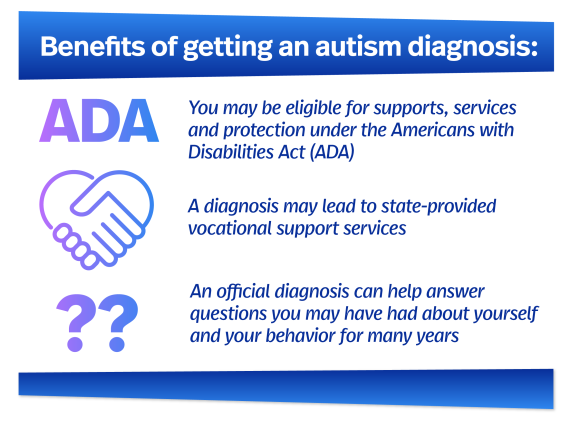

What are the benefits of getting a formal autism diagnosis?

Some people may be concerned that their child is exhibiting signs of autism but may not be sure whether a diagnosis would be helpful. There are several potential benefits for obtaining a formal ASD diagnosis.

Firstly, obtaining an ASD diagnosis opens the door to therapeutic services. This is especially critical for young children below the age of 5 because research has shown that children who receive intensive services early in life have the best chance of improvement. Many states have laws that require insurance companies to provide coverage for evidence-based interventions, such as Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) therapy, if a patient has a formal diagnosis of ASD. These services are prohibitively expensive for most families and usually aren’t feasible without insurance support.

Insurance is also more likely to support genetic testing if a child has a diagnosis of ASD. Genetic testing can sometimes identify other health conditions associated with ASD that wouldn’t be picked up otherwise. For example, there are genetic syndromes related to ASD in which individuals have a higher risk of colon cancer. In such individuals, early screening for cancer is recommended. In the future, we may have specific medical treatments for individuals who have different kinds of genetic syndromes associated with ASD, although that’s not something that is currently available.

Also, an ASD diagnosis may allow for additional levels of resources and support. There may be state agencies that can provide help for families if their children have a qualifying condition, including ASD. Depending on the family’s situation, their child may qualify for supplemental security income (SSI), in-home supportive services (IHSS) and/or handicapped parking access. If a child is not eligible for an individualized education program (IEP) through their local school district, a formal diagnosis can help parents establish a Section 504 plan to secure accommodations in school.

Finally, obtaining an ASD diagnosis can help caregivers better understand their children and help autistic people better understand themselves. I see this is especially true in my older patients who have ASD. Individuals with ASD may feel isolated or different from others and may have difficulty expressing or understanding themselves. Having the “label” of ASD can be helpful for some, as they may find a sense of belonging within the ASD community. Although each individual with ASD is unique, knowing that they are part of a bigger picture and learning how individuals with ASD have changed the world can help in establishing a personal identity and self-managing difficulties that may pop up along the way.

Learn more:

- DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for autism

- Learn about autism screening

- Read about the severity levels of autism

- Download the First Concern to Action Tool Kit to learn about the path to diagnosis

- If you are an adult and suspect you may have autism, download our guide for adults