Mom perplexed by toddler stimming

Replacement behaviors for stimming in toddlers

By Dr. Stephanie WeberToday’s answer is by psychologist Stephanie Weber, of the Kelly O’Leary Center for Autism Spectrum Disorders at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. The center and hospital are part of Autism Speaks Autism Treatment Network.

Our two-year-old has started running back and forth while shaking things – a string, wire, pencils, hangers, whatever – in his left hand. He does this for hours and has started doing it in public. How can I find a substitute for this behavior and/or limit the time he spends doing it? He has a fit if I take away what he’s shaking. But it’s becoming extreme, and people are starting to notice.

Thank you for your question. I hear similar concerns from many families whose children come to our autism center for behavioral therapy. It’s great that you’re being proactive in recognizing that these repetitive behaviors can become barriers to your son interacting with people who don’t understand them.

Before we get into why your son is doing these things and how to work with him, let’s first make sure he’s safe. So please take a look at the wires, pencils, hangers or other objects that he likes to shake and consider whether they could hurt your son if he, say, falls or shakes them too wildly. If so, it’s best to keep them – and other dangerous objects – out of his reach and sight.

Stimming in toddlers

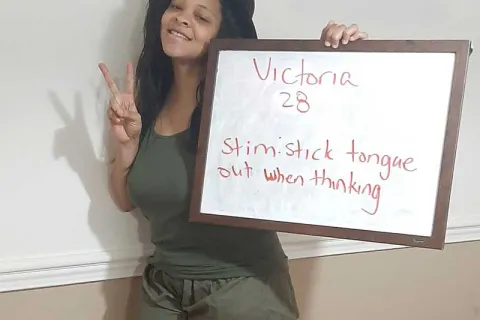

Many children and adults who have autism find it soothing to rock, walk on their toes, flick items in front of their eyes and flap their hands. These are just a few examples of autism-related repetitive behaviors that can be self-calming or self-stimulating, also referred to as stimming.

Understanding self-soothing autism behaviors

Are there certain situations that trigger this behavior for your son? If so, it may be that he’s using the behavior to calm himself. It will help if you can avoid or limit the triggering situations to the extent possible.

Helping your child with replacement behaviors for stimming

In any case, from your description of the way your son runs back and forth shaking items for hours, I think it’s very likely that it feels really good to him. In addition, your son may not grasp how to play the way other children do.

Many families come to me perplexed, saying “We have so many toys! I don’t understand why my child just wants to flick and shake things!” I explain that – despite having a wide variety of toys – many children who have autism don’t know how to play with them in the ways we expect.

The types of play we consider “natural” can seem confusing or frustrating to many children who have autism. As a result, they entertain themselves with activities just like the ones you describe in your question.

Learning how to play

My first suggestion is to help your toddler learn how to play with a simple toy. You might need to use gentle hand-over-hand prompting to show him how.

Hand-over-hand prompting is just like it sounds: You put one or both of your hands over his to guide his motions to complete a task. You can do this with many kinds of toys such as ring stackers, shape sorters, simple puzzles, activities that involve matching picture, putting pennies in a piggy bank … and the list goes on!

When teaching your child new ways of playing, make sure to provide verbal praise. For example, “Great job. You put the orange ring on the peg!” In addition to providing positive reinforcement, this helps your son build language and gives him specific information on what you’re expecting from him.

Redirecting and reinforcing

Many children who have autism aren’t easily redirected away from the activities they love. It sounds like that may be the case with your 2-year-old. Often a reward can help motivate a change. For example, does your son have a favorite video? You can explain that he’ll get to watch a short clip from the video after the two of you finish stacking the blocks together. Or perhaps he’ll be motivated by a few mini M&Ms or a hug and tickle. You know your son and what motivates him.

Communicating with visual supports

Some children with autism respond better to visual than spoken directions. Hasbro has created a number of visual supports, social narratives and “how-to” guides for helping children with autism learn to play in a meaningful ways. The Autism Speaks Visual Supports Tool Kit is another great resource.

Encouraging functional behaviors

Through the strategies described above, your aim is to help your son replace some of his “nonfunctional” behaviors with functional ones. By nonfunctional, we mean that the behavior isn’t helping your son communicate or connect with others or to accomplish a task – such as playing in a way that can build important skills.

At the same time, it’s important to remember that it does not work to take away a child’s favorite activities without giving him or her something else that feels good. That’s why the verbal encouragement and rewards can be so important as your son learns to enjoy playing in a more functional manner.

Time for self-soothing

It’s also important to build times into the day when it’s okay for your child to engage in the self-stimulatory behaviors that feel good to him. I suggest that you clearly explain to him when and where these behaviors are okay and when and where they are not appropriate.

Consider drawing up a short list of rules concerning when, where and how long your child can engage in the self-stimulatory behavior. For example, some families find it works to allow a child to engage in the behavior for a few minutes at certain times a day, but only at home. Some families encourage their children to engage in the behavior only in their own bedrooms. This has the added lesson of making clear that these behaviors are not appropriate for social settings.

You can plan for those times when the repetitive behaviors are not okay by having a favorite toy or other distraction ready to help redirect your child.

Keep using those visual supports

With a child as young as two, it will be very important to use pictures to go along with new rules. Visual supports can help you convey what you expect.

Along these lines, a visual daily schedule can help you make clear when different behaviors are appropriate. On the calendar, you can draw a picture to illustrate “Free Time” or “Sammy’s choice of activity” at the appropriate time or times during the day. Then teach your son – through lots of reminders and practice – that this is the time he can engage in his self-soothing behaviors.

Most two-year-olds are just learning how to stay focused on an activity for 5 to 10 minutes at a time. So timers can be another great tool to let your child know when one activity is over and the next one begins. This includes using the timer to show your child how long he can engage in his self-soothing behavior. When the timer goes off, it’s time to do something new.

It may help to give your child a special box where he can put away the string or other object he likes to shake. Then he knows it’s safe and waiting for the next scheduled time.

Another great way to use visual supports to direct your son’s activities is with a “First/Then Board.” The “first” picture shows the child what activities he or she needs to complete before moving on to a desired activity. For example, the “first” picture might show your child playing with the ring stacker. In the “then” box, you can put a picture of your son running back and forth with his string! Photos can be particularly helpful for young children who don’t yet understand that cartoon drawings symbolize real people and objects.

Once your child feels more comfortable with the new activities you’ve introduced (e.g. playing with toys) at home, I recommend introducing enjoyable activities that your son can do with the family in public. For example, reading a book together on a park bench or while waiting for a doctor’s appointment. Practice these new activities at home first and then try when out in the community.

Thank you again for your question!

Editor’s note: The above information is not meant to diagnose or treat and should not take the place of personal consultation, as appropriate, with a qualified healthcare professional and/or behavioral therapist.